With Russia and Ukraine, the Caucasus and Gaza, the West has shown dispiriting impotence.

One fine day in New York City I was applying for a job with the Associated Press when the international editor said: “How does Bucharest sound?” So began my quarter century or so as a foreign correspondent, one of the strangest and most wonderful ways to make a living in this life.

I was offered Romania because my parents had managed to flee the country some years before I was born, and unlike anyone applying for a job that day I spoke a version of the language. My parents were scandalized to hear of it.

I found Romania in a miserable state, weeks after the toppling of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu. There were no lemons nor pickles on the shelves, the currency had collapsed along with savings and pensions, dogs roamed every alley and every now and then miners rampaged in the streets. But an intoxicating optimism filled the air. From the ruins would arise a free country. I viewed all this as a triumph of the West. As a vindication of my parents’ emigration and a validation of all I had learned and absorbed. The West was the best, and the United States was the best of the West.

The zeitgeist was summed up in the book and essay by the American political scientist Francis Fukuyama known as The End of History. He argued that the great historical discourse had been decided with finality in favor of liberal democracy.

We young foreign correspondents bought this idea completely, and it extended to a notion that the era of great wars would also end. We thought reason would henceforth prevail because increasingly events would be transparent, people educated and prosperity global. No more slaughtering each other over a bit of land or a bowl of rice.

I was in the AP regional editing hub in Vienna on the day that the first several casualties occurred in Yugoslavia. I remember the shock. My managers, serious people experienced as hell, maybe 40 years old even, could hardly believe it.

We know what happened next, and it was not the end of history. The world that emerged looked closer to Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations – a global struggle driven by religious and cultural identity. While derided in some circles, he seemed to be on to something when he identified the main challengers to the West as the Muslim world and China.

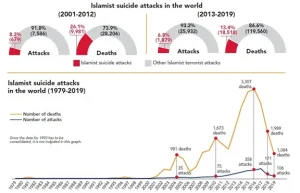

The result is evident in this study and the below chart showing the death toll from jihadi suicide attacks. The peak year was 2016, with 3307.

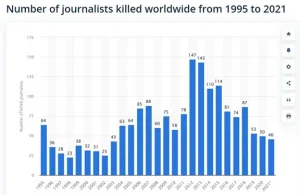

It’s also evident in this chart showing the number of journalists killed covering conflicts. The peak year in recent decades was 2012. According to the International Federation of Journalists, close to 3,000 journalists were killed worldwide in the past 30 years, most of them in war.

Which brings us to 2023, in which we’ve see three awful conflicts that gripped the attention of the Western world (and others in Africa, which disgracefully have not). The three wars were dissected on a conflict coverage webinar I was a panelist for last week (click here or below).

Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. By this summer US officials estimated that about 120,00 Russian soldiers had been killed, as well as at least 70,000 Ukrainian soldiers and thousands of Ukrainian civilians. Hundreds of thousands more have been wounded, in Ukraine millions have been displaced, and hundreds of thousands have fled Russia itself. The economy is surviving on wartime internal demand, but Russia’s prospects of integration into the world economy have been devastated. All this, so that the world’s largest country by territory might acquire bit more territory.

Next in 2023 came a rather incredible development in the Caucasus. The border between Armenia and Azerbaijan was an example of Soviet mischief, with Nagorno-Karabakh gifted to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan despite being an Armenian heartland for millennia. The result was a war 30 years ago, when the USSR disbanded, in which the Armenians established self-rule – and a more recent effort by Azerbaijan to reestablish control that began with a military assault in 2020. In that war, Azerbaijan regained much territory but not the core of the self-rule area.

In Dec. 2022 Azerbaijan began to blockade what was left, mainly around the town of Stepanakert. Two months later the International Court of Justice ordered Azerbaijan to end the blockade. That call was joined by almost every major government including the US. In August, with mass starvation in the enclave, international jurists led by the first chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Luis Moreno Ocampo, began to accuse Azerbaijan of genocide under Article 2C of the Genocide Convention.

None of that moved Azerbaijan, and on Sept. 19 it attacked the province. Swiftly the local authority surrendered and within days almost all 120,000 people fled, becoming refugees in Armenia. It was one of the largest mass exoduses in recent history.

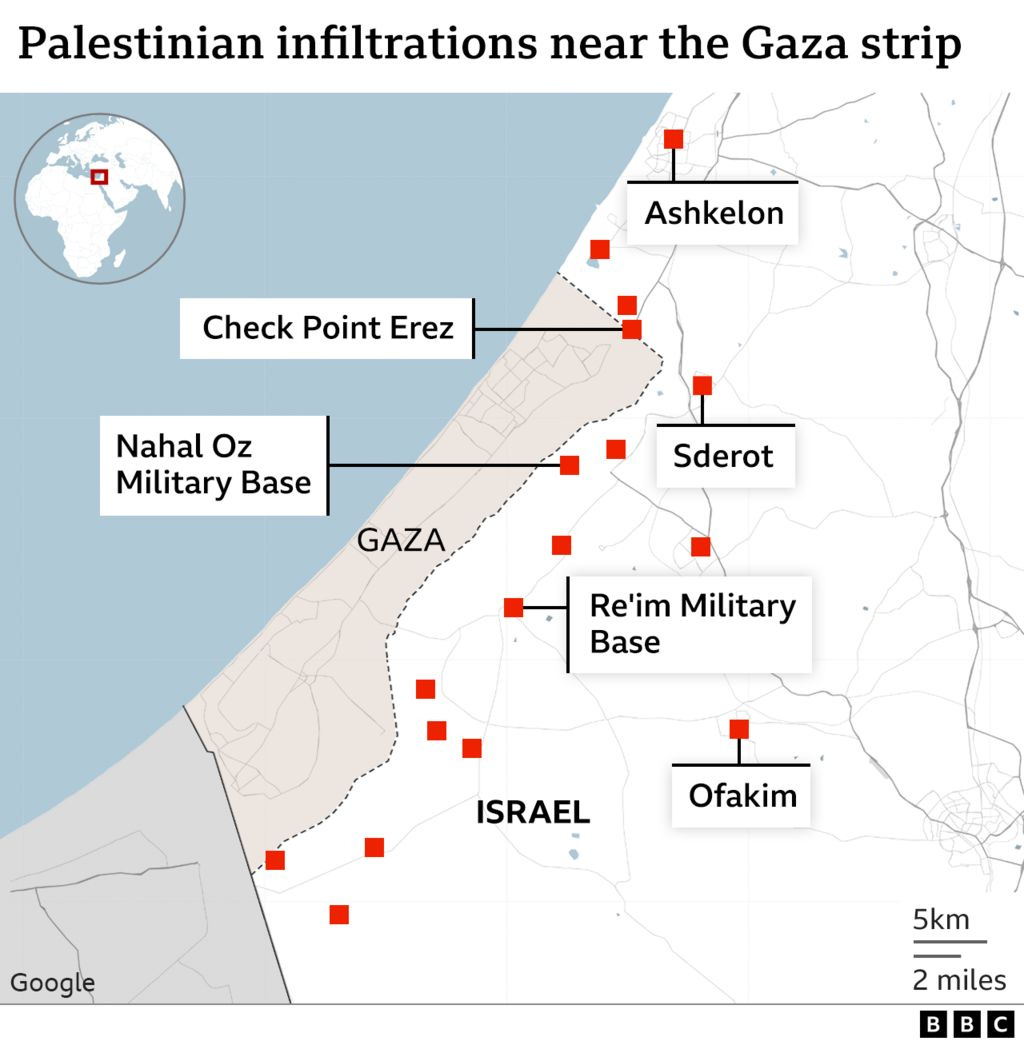

And now comes a war between Israel and the terrorist group Hamas, sparked by the massacre in a single day of 1,200 Israelis in an invasion from Hamas-run Gaza on Oct. 7. Israel decided to tolerate Hamas in power in Gaza no more, and thousands of Gazans — systematically used by Hamas as human shields — have been killed in its devastating counterstrike.

The war could escalate dramatically in myriad ways. Most obviously, the Hezbollah militia in Lebanon, which like Hamas is an Iranian proxy, could join in and do enormous damage because it has tens of thousands of powerful long-range rockets. Already it has been provoking Israel with sporadic rocket fire and shelling.

The United States, which has two major carrier groups in the eastern Mediterranean, has made clear that it will defend Israel if needed, and it is not inconceivable that US military planners would relish a chance to destabilize Iran and perhaps compel regime change there. If Iran is attacked by the US from its bases in the Gulf (interestingly the main one is in Qatar, which is close to Iran), then Iranian action against America’s Sunni allies like the Emirates and Saudi Arabia is not inconceivable.

What if Saudi oil installations were attacked by Iran or its proxies and the Straits of Hormuz were blocked? What would this mean for the world economy? Might China use a moment of such distraction by the West to make a move on Taiwan?

Moreover, it is difficult to predict what Israel might do in this kind of a full-blown conflict. If it feels it is under existential threat, the first use since Nagasaki of nuclear weapons in conflict is not impossible to contemplate. What would follow from such a catastrophe is as difficult to predict as the danger is impossible to overstate.

What can we learn?

For one thing, the asymmetric warfare in the Middle East underscores a democratization of destructive force. As technology advances, this places incredible power in the hands of small groups of people, even individuals. Just as every person is now a publisher on social media, so might in the future one person be able to poison the water supply or deploy weapons of mass destruction. The most deadly day in the entire history of Israel was brought about not by a major army but a ragtag outfit armed with guns, knives, blowtorches, and video cameras to record the butchery.

A related phenomenon is an epidemic of poor governance that enables and amplifies the concentration of places in the hands of a few — often either malicious or incompetent. You could argue that all three events happened either because of the whim of one man or a small group.

Sure, many Russians think Ukraine is a fake country. Russia has economic interest in the mineral-rich regions of eastern Ukraine and territorial grievances that relate to more Soviet monkey business with internal borders. But that was true under Boris Yeltsin as well, yet an invasion was unimaginable. I’ve heard no convincing case that this was not the obsession of one person out of 140 million Russians – Putin.

In the Caucasus, what happened was the result of Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s single-minded determination to restore full Azerbaijani control to Nagorno-Karabakh, and he had been heating up his anti-Armenian rhetoric for years. Here too you could argue national interest, but the risks and the costs are high: Azerbaijan risks becoming a pariah state, especially when its natural gas runs out. Aliyev’s family kleptocracy needs the distraction of conflict to keep the population at bay.

Which brings us to Gaza. Hamas is run by a few bad men whose major actions need greenlighting by its patron, Iran, which is itself run by a small clerical clique. Iran was observing with dismay the willingness of its rival Saudi Arabia to make peace with Israel in the framework of a strategic agreement with the United States that might have included a US-sponsored civilian nuclear program. It needed a massive Middle East war to delay or scuttle these plans.

So there it is: A small collection of miscreants who could fit comfortably in my living room causing incredible damage to the planet against the manifest will of West. The West did not want Russia to go berserk and risk nuclear war (and despite aiding Ukraine has not prevented an ongoing disaster). The West tried in vain to stop the blockade and avoid the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh. The West has been impotent to prevent funding to Hamas, even though it has leverage over Qatar, also a major patron of the group.

Why is the West so weak? There are some obvious answers.

Economic power is moving east, as Huntington foresaw. Hegemony is a thing of the past. And globalization has created interdependencies – not just with energy but in other trade and about technology – which make interests and desires collide. Europe still needs Russian natural gas, even if consumption was reduced. The US needs trade with China: Over 7% of US exports go to China and 18% of imports come from it. And the US is exhausted after the Iraq and Afghanistan wars ended rather badly.

But there is something else happening, I do believe: An internal weakness of the West caused by corrosion in society, which results from an unfortunate imperfect storm.

There is frustration at the fact that the middle class has not seen living standards rise in about 40 years, mostly because of globalization moving blue collar jobs to developing countries. There is frustration that digital disruption has reduced the available jobs that don’t require extraordinary education and ability. There is frustration that as a consequence of this and of other demographic trends there are very few lifelong careers or pension plans.

And there is tension between ethnic groups because of migration. The mixing of civilizations, if you will. Even though this brings benefits, many people just seem to hate it.

This was the landscape as we entered the social media age. It was once thought that the digital ecosystem would foster debate and tap the so-called “wisdom of the crowd” – but instead we find that the algorithms, to maximize engagement, create echo-chambers where like-minded extremists drive each other into a frenzy. It’s just math meeting human nature; unless we force regulation, there is not much to be done.

On top of that we have bot armies with fake accounts driven by interests both overtly political and disturbingly shadowy. The social media sentiment firm Cyabra reports that on Oct, 18, when a Gaza hospital was struck (apparently by an errant Palestinian rocket), 35% of conversation on Twitter on the issue was generated by fake accounts.

Thus arrives extreme polarization. We have ended up, in the West, with both an extreme right which can be xenophobic, aggrieved, and given to conspiracy theories — and an extreme left that is illiberal and humorless, obsessed with narratives of oppressed and oppressor and anti-intellectual. It also yielded a postmodern false equivalence that accepts all narratives as lived experience and a disrespect even among intellectuals for the concept of objective truth. When identity politics – emphasizing tribes over the nation and race over humanity – become everything, society becomes too divided to save itself, let alone lead responsible global governance.

There once was wide agreement in the West on the principles to stand up for: reason, freedom, and decency. The West has not always represented those values, of course, and it has a lot to atone for — yet over the past century of so, that was the ambition and it played a useful role in the world. But the West is now rotting and the common ground gets smaller all the time. Soon it will not even agree internally on the concept of Western civilization; indeed that day may have already come.

Our friend Fukuyama put it well in his most recent book, Liberalism and its Discontents: “The type of liberalism that seeks to be relentlessly neutral with regard to ‘values’ eventually turns on itself by questioning the value of liberalism itself, and becomes something that is not liberal.”

In such a situation there will be little to deter the nasty and the brutish from making the world a jungle. It is a field day for the cynical.