Sometimes our assumptions are so ingrained that we hardly notice they’re assumptions. So it is with the widespread conviction that freedom and democracy are natural parts of the same whole, or that repression and democracy are at odds. But that is not exactly so. 9/11, for example, was an assault on our freedoms.

So it is ironic that as we remember that history-altering terrorist attack on this date by Al Qaeda, we also find ourselves before an election year when the US electorate might democratically choose a leadership that will undermine those same freedoms.

As for democracy, we should know what we’re talking about when we throw around the word. Derived from ancient Greek, it has been around since before Socrates, and yet it would be reasonable to say that there were no real democracies until a century ago, when women first won the right to vote in New Zealand (it was the first), Britain, the United States and a few other places.

There have been many kinds of „democracies.” Some of them don’t look quite right to most Western eyes at all. And yet, it was not just mindless propaganda when the communists referred to the police state of East Germany, without a trace of irony, as the „German Democratic Republic.”

This seeming linguistic oddity was based on Marxist-Leninist principles, which once mattered to many people. These held that capitalist systems benefit only the bourgeoisie, while the majority of people, the working class, are so enslaved to their jobs that they are easily manipulated and have no real choices. That the „system is rigged,” which perhaps will sound familiar. It may not suggest much respect for the fortitude of the common man, but is it nonsense?

When they were still wrestling with ideas as opposed to robbing people blind, the communists believed the communist system—a „proletarian democracy”—served the broad majority of working people. It didn’t quite work out that way because it failed to yield prosperity, but that’s not exactly a matter of democracy.

The word „democracy” continues to be twisted in all directions, as we see in the case study known as Israel under the Putinesque incarnation of Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Netanyahu government wants to install an authoritarian-style system in which the executive branch has almost unlimited power. Under a series of proposals currently delayed because of massive protests, the government would directly appoint all the judges, seriously defang judicial oversight, also grant itself „override” powers, and drastically weaken the gatekeepers. Serious mojo for the government; not much left for the people.

They argue that this is „democracy,” because the ruling coalition won an election last November. The election was basically a tie, Netanyahu had hidden his intentions, and the plan is very unpopular—but let’s put all this aside, because the mere possibility that the people might choose such an attack on themselves is worth examining. Netanyahu’s democracy is majority rule and little else.

The opposition and protesters in Israel demand the plans be cancelled and that Israel enact a constitution, and they have united around a single word. That word is chanted by little girls carried on the shoulders of parents at the weekly mass rallies against the plans. Can you guess what that word is? In Hebrew it is pronounced „democratia.”

Their version of democracy involves fine things like checks and balances, minority protections, human and civil rights and lots of basic freedoms. In this version, a majority cannot be permitted to oppress the minority even if that is its desire. There is an accepted term for this version of democracy, and that is liberal democracy.

That is the version of democracy that has been implemented in the United States—pretty much from the beginning, if you ignore the disenfranchisement of women and African-descended slaves (which, yes, would be odd, but people do it).

Many Americans may be confused about the fact that theirs is a liberal democracy because the Latin-origin word „liberal” has itself been bent out of shape in the US Somehow it has come to mean leftist. That is about as rare a definition of the word as is the use of the Imperial system of measurement. And like the use of inches and ounces, it is basically just plain wrong. It becomes increasingly absurd once you notice that today’s far left in the US, at least when it comes to free speech, is about as liberal as Mussolini.

Liberalism stands for freedoms, just as it sounds. Britain’s John Locke, one of the fathers of liberal thought, argued that individuals possess natural rights, including the rights to life, liberty, and property, and that even when not granted by governments they are inherent to human beings. He called for a „social contract” between the government and the people, to ensure the respect for and promotion of those rights.

The US „framers” added the „pursuit of happiness” to the list of natural rights, and ours is not to quibble.

The assumption that people desire these things is engrained in the American psyche and reflected in America’s behavior. Even the so-called Bush Doctrine of the 2000s, while aimed at foreign policy goals, espoused democracy and freedom and seemed to assume, with ill-advised indifference to cultural realities in various places, that this would yield stability as well as happiness.

The failure of that assumption soon became evident. You can see the results in Afghanistan and Iraq; in the deep freeze that replaced the Arab Spring; in Hungary, Poland, Turkey, Brazil, and more—all places where democratically elected authoritarians hold sway.

It could happen in France and elsewhere in Europe too. Israel is teetering on the brink. And that brings us to the United States.

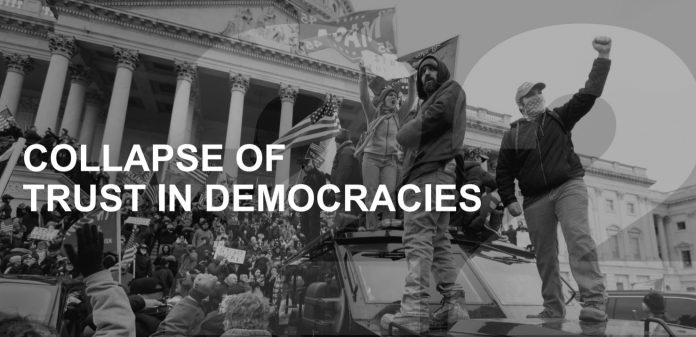

You could say the people didn’t quite know who they were voting for in 2016, but now we know. About half the voters in 2020 still backed Donald Trump, and next year they might do so again.

There is no way Trump can be seen as a liberal democrat. He clearly projects no fidelity to Locke’s theories. He will not only happily take away abortion and other freedoms, but he also cares nothing about any social contract. Certainly not one that provides citizens with a baseline of health care and protection from gun massacres. If you ignore his efforts to overturn the 2020 election (as well as the strange outcomes of the Electoral College), you might say Trump’s democracy is, just like Netanyahu’s, about no more than majority—or dishonest minority—rule.

That makes Trump sound the same as Viktor Orban of Hungary, and Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey. Then again, his legal woes — scores of felony charges beginning with the Stormy Daniels hush money case in March — are most reminiscent of Netanyahu.

But what about all the people who vote for these unliberal democrats? What about the 40 percent of French voters who backed the decidedly illiberal Marine Le Pen in last year’s presidential election?

A few percentage points to this side or that may decide elections, but cannot obscure the obvious truth: liberalism, hugely popular among educated elites, is at best a nice-to-have for the masses. I’ve covered elections from Romania to Ramallah and have observed this everywhere, with the possible exception of the contented Nordics.

That’s because democracy and liberalism are distinct political concepts.

Liberalism seeks to protect individual rights and freedoms, even if that goes against the will of the majority. Liberalism prizes freedom of expression, including for unpopular opinions. Liberalism emphasizes civil liberties and privacy rights and limits government power to do what a majority wants. It insists on capitalism (but with a safety net), whereas democracy can bring a communist to power (as has occurred in Latin America and elsewhere).

And democracy might elevate theocracy. That’s why I say the 9/11 attacks were mainly against liberalism and freedoms. In the Arab world, where I lived for years, many members of the elite were no fans of democracy, because they feared that the masses might be tempted to elevate theocrats. That is why the military’s overthrow of the Muslim Brotherhood government in Egypt in 2013 was not initially unpopular among the educated classes who basically favored Western-style freedoms above all else.

So, if supporters of liberal democracy were honest, they would ask themselves the question: Am I truly a democrat first and foremost? Which of the two words in the label matters more? At the end of the day, is it liberalism you believe in, or the people’s choice? Consume enough beers, and you may shock yourself with your own answer.

Do not be too surprised when right-wing populists call you an elitist. You may just have to own it.