Many have wondered what it is about Benjamin Netanyahu that so upsets some people. After all, this erudite man in his 70s towers intellectually over most world figures and remains a ball of energy after a lifetime in public service.

Despite his qualities, the other side loathes him in a way that transcends politics. His own former allies defected one by one to the opposition until he was dethroned in mid-2021. And his main partner today, Bezalel Smotrich, was recently caught on tape calling him “a liar, son of a liar” (which seems unfair to Netanyahu pere).

I believe my own encounters with Netanyahu might shed a bit of light on the mystery.

I first learned of him when I was a student in the US and he was a regular on ABC’s “Nightline” with Ted Koppel. His English was flawless and almost unaccented, but with just the right trace of foreignness to make him impressive as a non-American. While he was dogmatic, he showed some capacity for dialectic. And despite surface harshness one sensed the trace of a smile that hints at inner humor, creating empathy in the viewer.

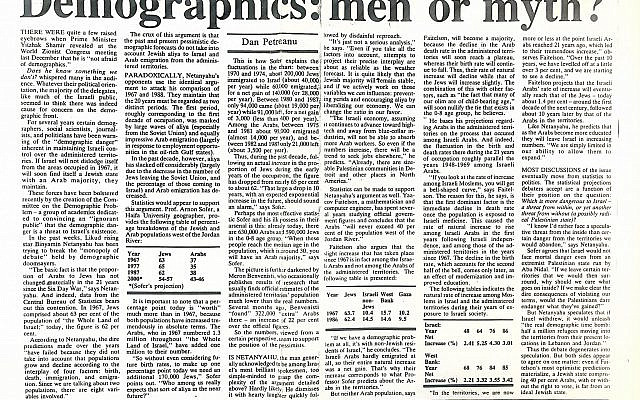

I was genuinely excited to find myself interviewing him only a few years later, as the embarrassingly young political reporter for the Jerusalem Post. Netanyahu had returned to Israel as a highly touted Knesset candidate, and I was writing about the demographic aspect of the West Bank and Gaza occupation.

My own position then was exactly as today: that while Israel has a good security case for holding on to the West Bank (and a weak one for Gaza), the point was moot since it cannot absorb so many Palestinians. It risked becoming an ungovernable and undemocratic binational state.

Liking and respecting Netanyahu, I hoped that he might nudge Likud away from its suicidal blindness to this. I had the right idea but the wrong guy; this eventually happened with Tsippi Livni, Ehud Olmert, Ariel Sharon and others, but with Bibi it was not to be.

In this 1988 interview Netanyahu conceded nothing, offering misleading analyses and inaccurate predictions, yet with such flourish that one was mesmerized.

Speaking the same excellent English, he said demographic predictions “have failed because they did not take into account that populations grow and decline according to the interplay of four factors: birth, death, immigration and emigration. Since we are talking about two populations, there are eight variables involved.”

Eight variables! Interplay!! Who in politics says things like this?

“It is quite likely that the Jewish majority will remain stable, and if we actively work on those variables we can influence, preventing (emigration) and encouraging (immigration), (and) by liberalizing out economy, we can change the ratio in our favor.”

The Jewish population then – all agree – was just over 60% of the combined area of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza. Since then Israel indeed controlled “the interplay” of key variables, and a million Soviet immigrants unexpectedly arrived to boot. Yet Jews and Arabs are now evenly divided in the territory, exactly as all professionals foresaw.

Netanyahu also inaccurately predicted mass Palestinian economic emigration, since “assuming (the economy) continues to advance toward high tech and away from blue collar industries, we will not be able to absorb more Arab workers. So even if the numbers increase, there will be a trend to seek jobs elsewhere.”

The obstinacy made me sad, yet I realized his alpha delivery would win hearts and minds. There was potential here for a highly successful demagogue.

I would meet Netanyahu again in 1996, in the last days of his campaign against incumbent PM Shimon Peres, who succeeded Yitzhak Rabin after his assassination. Netanyahu was Likud leader by then. Since the Oslo Accords – which he had bitterly opposed – set a May 1999 deadline to reach a final peace agreement, I asked Netanyahu what he’d have to offer.

“Young man,” said Netanyahu, “I will offer them autonomy.” But the Palestinian Authority already had “autonomy,” I protested. “They want independence.”

“Young man,” he said. “Have you heard of the Catalans?” Before I could answer, he explained that this Iberian tribe lived under an autonomy arrangement and sufficed with it, “even embracing it.” I replied that the Catalans were also citizens of Spain who vote for the same parliament as everyone else; was this what he would offer the Palestinians, giving them half the Knesset? Netanyahu looked around, saw there were no TV cameras, told me “I’ll be back,” and was gone.

And here’s the thing: Netanyahu seems foolish (because his analogy was false) but he was actually smart (because most listeners would have not seen it). His goal is not a professorship in comparative politics, but votes. And his method of selling snake oil is confident eloquence. This works, and it is exasperating to political opponents. It gets them wanting to scream at anyone who buys it – as we see happening today.

In our third conversation, in an AP interview in 2002, I found a darker Netanyahu. He had been defeated by Ehud Barak in the direct election of 1999, and now found himself on the sidelines of Ariel Sharon’s government. He was as colorfully articulate as ever — calling the Palestinian Authority a “corrupt, backward, primitive regime” – but also radiated a brooding suspicion that bordered on the hostile. Sharon was popular, and few were looking to Netanyahu for answers. The press was largely against him, and he returned the favor.

Yet Netanyahu in subsequent years as finance minister did something very right: still a committed free marketeer, he bravely slashed subsidies which had disproportionately gone to the Haredi sector, in hopes of nudging them into employment.

Netanyahu returned to power in 2009, backed by the same Haredim, and now the subsidies are back, and bigger. So is the West Bank settler movement. In his 13 extra years in power Netanyahu dragged Israel significantly closer to a failed economy with a Haredi majority among Jews (if nothing changes at most 50 years away, given the sector’s birthrate of over 8 children per family) and the binational state scenario.

A series of corruption scandals ended up with Netanyahu on trial for fraud, breach of trust and bribery, yet clinging to office and now, at 73, running for the country’s leadership once more.

It is breathtaking to recall his 2009 admonition that Olmert resign because of a mere investigation. “A prime minister up to his neck in police investigations,” he said with his customary confidence, “has no moral and public mandate to determine critical things for Israel, since there is a not unfounded concern that he will decide based on his personal interest – for his political survival, and not in the national interest.”

Such hypocrisy (from a once-outspoken advocate of a two-term limit) does not sit well with those who notice it or care, and creates toxic divisions versus those who don’t (and don’t). It is of a piece with Netanyahu’s persuading of a key Haredi group not to agree to a desperately needed core curriculum, as they were about to, and his successful scuttling of visa-free travel to the US, so Prime Minister Yair Lapid would not get the credit. No joke.

Should Netanyahu win the Nov. 1 election in a coalition with far-right nationalist and Haredi parties, the main plan is to pass an “override clause” to enable parliament to cancel decisions of the courts. This starts to take Israel down the path to a Jewish version of Turkey. Expect hysterical opposition – and rage at supporters of it.

My last meeting with Netanyahu was in 2018, when (as AP’s Cairo-based Middle East Editor) I had the highly coveted first question at his annual meeting with the foreign press.

This event is remembered for the tricking of illusionist Lior Souchard, whom Netanyahu challenged in unplanned fashion to guess what he had secretly drawn on a piece of paper. Souchard tried evading the gambit, instead (correctly) guessing the PIN number of one of the journalists, but Netanyahu wouldn’t let it go until the poor man admitted failure; his unsporting host had drawn a menorah, it emerged.

My own bit was less awkward, but not by much. I asked the prime minister whether it truly did not bother him that the overwhelming majority of his own peers – secular, educated Israelis – oppose him with increasingly urgent vehemence.

“They not only oppose you, but they think you are leading the country to absolute and irreversible ruin,” I continued. I told him the toxicity was unbearable, and that it was fascinating to contemplate that this bothered him not at all.

Netanyahu ignored the question and asked me whether I wanted to switch places – “because it sounds to me as if you want to be the one who is on stage.”

He was certainly right about that, and I thought to myself that he remained the same clever man. But then I noticed something subtle but significant. The smile I remembered from Nightline was gone. The humor had curdled into cynical bitterness by now, as humor often does, when a person feels besieged.