Laurentiu Mihu contributed to this report.

BBC journalist Nick Thorpe arrived in Bucharest shortly after the November 1987 workers’ riots in Brasov and headed to the British embassy for a beer and a chat.

There, a British diplomat engaged in small talk before sliding his business card across the table and gesturing to Thorpe to turn it over. On the other side, there was a name and a telephone number: Silviu Brucan and how to reach him.

ATMOSPHERE OF FEAR

The moment revealed the level of psychological fear that gripped Romania in the final years of Nicolae Ceausescu’s rule and would overshadow Thorpe’s assignment to Romania which eventually saw him barred from visiting until the 1989 revolution.

Summing up the episode, Thorpe remarked: “So here we are in 1987 in Bucharest and a British diplomat does not feel free to speak openly even within the club deep inside his own embassy.”

The next day Thorpe called the number from a phone booth on the street and went around to Brucan’s house in the upscale Herestrau Park area in Bucharest, together with Pat Koza, a colleague from the American news agency UPI.

FIRST SPLIT IN THE COMMUNIST PARTY

The pair had little idea who Brucan was until he showed them pictures of himself with U.S. Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford and handed them two pieces of paper, one with his CV detailing his past as Marxist and career as a top diplomat, and the second, a statement on the Brasov uprising which had taken place earlier that month.

It was a defining moment in Romanian history: the first time a high-ranking communist official had publicly broken with Ceausescu.

The statement said something like “the workers’ demonstration in Brasov shows that the cup of suffering of the Romanian working class is overflowing,” Thorpe told universul.net.

“It was a remarkable letter that this man very close to the regime, breaking with it and saying the poverty, the suffering in Ceausescu’s Romania was too much, and as a Marxist he was worried about rupture would take place between the Romanian people and the party which he was still a prominent member of,” he said. Brucan then told them off-the-record what had happened in Brasov.

PHYSICALLY SCARED

Aware of the significance of the story he was about to report, both in Romania and abroad, Thorpe became even more concerned.

“We were very worried if the party knew, if the Securitate (Communist secret police) knew that we had that letter, perhaps we’d be involved in an accident. We were actually physically scared of what might happen to us. We thought the Securitate might try to stop us getting news of the letter out of Romania, so we decided not to try and report it from Romania.”

FOLLOWED BY THE SECURITATE

Openly followed by the Securitate “to intimidate us” and ever more fearful of what might happen to them, the pair set off to Brasov to try and get eyewitness accounts of the Brasov riots.

We asked people in the street “speaking German or French or English, ‘What is the way to the Black Church? We are journalists from America and Britain; what happened last week?’ in one sentence”

Some people scuttled off, others actually gave directions, and “and a couple of brave people told them, ‘you go left, right, straight on, 10,000 on the streets, and many people have been arrested’ and they would walk on and we would thank them politely.”

ONE BRAVE MAN

Finally, they met Mihai Barsan, a worker who had taken part in the riots and spoke “rather good English.” He told them to meet him later that evening at a bus stop. Being careful not to be seen with him, they followed him to his apartment where they stayed until two in the morning listening to his account of the riots, before returning to the hotel and leaving Romania the next day. Koza went to Bucharest where she flew to Warsaw, Poland, and Thorpe had a first-class train ticket to Budapest.

“We agreed to talk when we got home, we were pretty scared… we had eyewitness reports. It was a precursor of the 1989 revolution,” although they didn’t know it at the time, he said.

TERROR ON THE TRAIN

By this time, the fear was mounting. Thorpe didn’t know whether he would be able to leave Romania and wondered whether the Securitate would try to set him up. Drops of cold blood fell on to his head from a parcel placed on a rack above where he was sitting on the train, only heightened his anxiety. “I hadn’t slept for two nights, it was too strenuous, too exiting, too dramatic.”

He memorized the statement.

Anxious that it would be taken from him, he went to the toilet and tried to slip the piece of paper behind the toilet mirror when a guard burst in. Thorpe’s trousers were around his ankles, but his only concern was whether the conscript had seen him and would report to senior officers.

He returned to the compartment, screwed the statement up into a ball and threw it into the rubbish bin which was full of apple cores and cigarette butts. At the border, guards took away Thorpe’s suitcase and notebooks, something he had anticipated. He had disguised names and numbers, and in any case, his writing was hard to read.

He eventually returned home, called Koza, and they simultaneously filed their stories.

“We released the reports to a rather surprised world,” Thorpe said.

BANNED FROM ROMANIA

But the exclusive and brave reporting meant that Thorpe was a persona non grata in Romania and banned from entering, until the revolution, when he decided to return with a BBC crew.

FIRST WESTERN CORRESPONDENT IN HUNGARY

Thorpe, now 59, was the first Western correspondent to be based in Hungary, moving there in 1986 where he reported on the region. In 1996, he became the BBC’s Central Europe correspondent.

He wrote ’89: The Unfinished Revolution – Power and Powerlessness in Eastern Europe describing the revolutions in Eastern Europe and the war in Yugoslavia, and in 2014 he published The Danube – A Journey Upriver from the Black Sea to the Black Forest which has been translated into several languages including German and Hebrew.

AH, MR.THORPE….

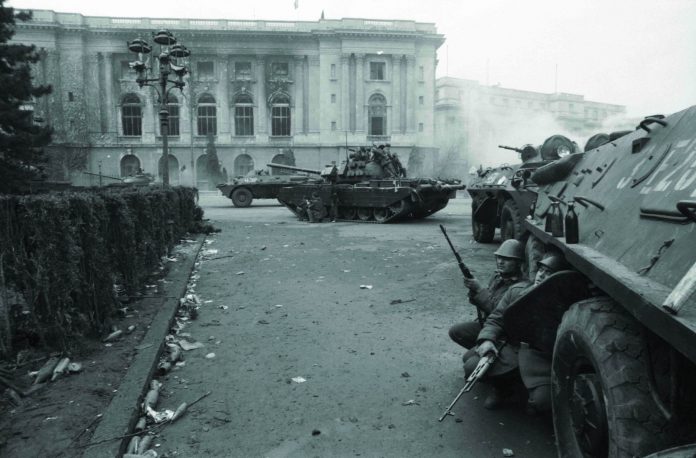

Thorpe returned two days after the Ceausescus had been executed, and remembers seeing how the center of the Romanian flag had been cut out. “It was a bitterly cold, snowy, icy day,” he recalled.

Border guards looked at his passport and said “Ah, Mr. Thorpe, are you planning to go to Brasov? And I said: “Yes, among other places.”

“They said: ‘welcome to Romania’ and they handed me a bottle of palinka or tuica, and it was very surreal,” he said. “It is the only time in my life when I have ever crossed the border and drunk hard alcohol with border guards.”

“There was that feeling of euphoria and celebration.”

BACK TO BRASOV

Thorpe went to Brasov where he looked for Mihai Barsan. “I’d been worried for two years, I had no contact with him. For two years I wondered what had happened to him if the Securitate found out he’d spoken to us.”

“It turned out that the Securitate had been following us on that November evening, they had a transcript, they’d been listening from nearby, they knew every word he’d told us.”

Barsan had been taken to Bucharest with others who participated in the riots and the van that transported them stopped several times. “They were told they were going to be shot…He was terrified to death.”

Barsan was sent to eastern Romania and sentenced to hard work and after 12 to 18 months he was finally allowed back to Brasov.

RISKING HIS LIFE FOR FREEDOM

“We had an emotional reunion and he told me he never regretted risking his life for and never regretted the pain that he suffered, the fear that he suffered,” Thorpe said.

“One of the questions I asked him back in November 1987 is “why are you risking your life to talk to us at 2am in the morning?”

He told Thorpe that he’d heard an interview with Argentinian leader General Leopolodo Galtieri during the Falklands war on the BBC. “He thought that if Romania was ever free, that is what a Romanian radio station should do… that is the essence of media freedom, to interview the leader of your greatest enemy.” Thorpe stayed in contact with Barsan and his family. Barsan is no longer alive, but his bravery and testimony remain.

His belief in press freedom “was the essence of his bravery.”