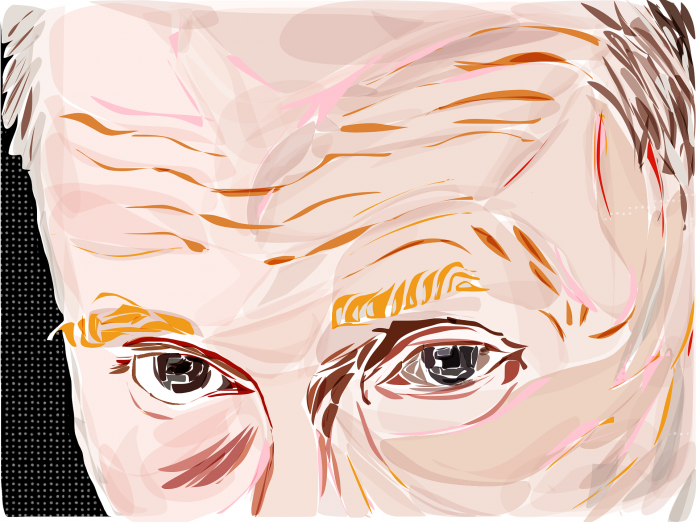

Tragic as the Ukraine crisis is, Putin is leading an even more dangerous assault on the rules-based world order, writes Dan Perry in an op-ed originally published in the New York Daily News and reprinted with permission in Universul.net .

About 14 years ago, we started hearing about a “credit crunch” and “U.S. subprime crisis” — but these labels did not begin to capture the essence of the global meltdown now known as the Great Recession. A similar diminishment is happening with the “Ukraine Crisis”: hard as it is to believe, we have an even bigger problem, and its name is Vladimir Putin.

The war Putin has launched against Ukraine undermines — and in an extreme scenario may even erase — the independence of one of the largest countries to emerge from the wreckage of the Soviet Union. This is an assault on a central tenet of the global post-World War II order: the inviolability of borders recognized by the United Nations.

This civilizing idea was not always adhered to, obviously: Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990 and Putin himself invaded Ukraine’s Crimea Peninsula in 2014. But generally, major powers did not simply gobble up other countries via military invasions. An invasion of Ukraine, if not forcefully repulsed, would constitute a major statement that jungle rules are back.

Incredibly, though, this violation of a fundamental principle of global order would not be the worst of it.

An unsentimental survey of Putin’s actions and statements in his two decades of rule strongly suggests that he is strategically dedicated to undoing the collapse of the Soviet Empire, which in 2005 he described as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the (20th) century.” It was a statement that people heard while choosing not to listen.

Undoing that supposed catastrophe would be about more than restoring to Russia an empire of its former dominions, though this surely is a motivating factor. It would also be about reestablishing the global relevance of the Soviet way.

Contrary to popular belief, the USSR was not, in its later years, much concerned with the utopian economic philosophies collectively known as communism. I traveled all over the USSR and Warsaw Pact as a young reporter for the Associated Press; let’s just say the workers did not control the means of production.

No, it was something else. The Soviet empire was the opposite of an egalitarian society. It was a highly stratified system that was about control as opposed to ownership, where several levels of grasping, cynical nomenklatura controlled everything worth controlling. Membership in these elites was a function of connections and loyalty. It was a kleptocratic dictatorship where the most craven brand of politics determined the ruling class (even more than in capitalism).

Putin’s “catastrophe” can be summed up in the sweet delusion of U.S. historian Francis Fukuyama’s “End of History” idea: that the principles of liberal democracy had prevailed so completely in the war of ideas that debate was no longer possible.

That notion also animated that part of the fancifully named “Bush Doctrine” that sought to justify the 43rd president’s “war on terror” by casting it as a crusade for democratic values. “Freedom is the right of every person and the future of every nation,” he then declared.

Anyone doubting that these notions are anathema to Putin might consult the Russian leader’s 2019 interview with the Financial Times in which he praised the rise of populism in democratic countries, said multiculturalism was “no longer tenable,” and argued that “the liberal idea has become obsolete” since it has “come into conflict with the interests of the overwhelming majority of the population.”

To clarify for the American reader: Putin is using “liberal” in the global sense. It is not about the Squad or Bernie Sanders but about a rules-based order, equality under the law, freedom of speech and assembly, protection of minority rights, checks and balances and separation of powers. It is, in short, about the animating principles of the American Republic.

This idea of the Russian Empire as a global power dedicated to the illiberal idea is why he sent his bot battalions to help bring about the election in the United States of a mega-disruptor like Donald Trump. It is why he helps conspiracists and xenophobes wherever they may roam — in France, Hungary, among the Brexit crowd in Britain. It is why he’s happy to prop up dictators like Bashar Assad in Damascus.

It is why he has no problem violating the norms of international conduct with bizarre assassination plots in foreign lands (and in his own). It is why he is shameless about setting up a fake democracy in which he claims a popular mandate despite the oppressing (or jailing) of the opposition, courts that are captive and media that is cowed (or wholly owned).

It is also why without compunction he invents fake news that will be presented as real by the pliant and fearful domestic media. Lies, in this meta-mindset, are more important than the outcomes they promote. They are critical in the very fact of their untruth because the detested liberal system depends on fact-based dialectic and reason. It is not for nothing that the three principles of George Orwell’s “1984″ dystopia were “war is peace,” “freedom is slavery,” and “ignorance is strength.”

The Ukraine Crisis can go any number of ways. Putin could gamble on a true total occupation despite the terrible price it will exact on Russia too; he could suffice with smaller incursions and occupations of the kind already visible in the country’s south and east; he might even back down a little after the first shots across the bow and keep fomenting mayhem via Russian insurgents in places like Donbas. Either way, he will invent a victory narrative that will probably involve the Western hints, already audible, that Ukraine joining NATO is not really in the cards.

Whichever way the Ukraine Crisis goes, the Putin Crisis will go on. It is clear that he enjoys messing with the West (perhaps the sole manifestation of a Putin sense of humor). He surely savors seeing stock markets tumble, making NATO look impotent, and casting himself as The Decider.

Embittered people all over the world will admire his bullying ways and smirking disdain for a liberal order that they feel has let them down. I have seen this in Cairo and Jerusalem, among Euroskeptics in Europe, and in the U.S. among acolytes of Trump, who was recently heard from calling Putin a genius.

When Samuel Huntington argued in his 1996 “The Clash of Civilizations” that the modern conflict was between a liberal democratic West and societies that rejected that worldview, this was widely understood to refer to the Islamic world. Putin is showing us that there is indeed such a clash, but the illiberal side is much broader.

The more he wins, the more the illiberal sentiment spreads around the world and also seeps into the West. Along with China’s alternative model for growth without freedom, it constitutes a major assault on the fact-driven, rules-based world order that the United States has championed.

While Putin is an agent of global damage, he is also a despot who needs to avoid a Moscow version of the Bastille. Rare is the political figure who can pull off such global disruption while being a petty tyrant at home.

Dan Perry is a former Mideast/Europe/Africa Editor at the Associated Press and currently managing partner at @thunder11PR.

(This article is republished with the kind permission of the NY Daily News).

British PM Boris Johnson vows massive sanctions to ‘hobble’ Russian economy